HMNs take a grand tour!

by Anna Maria Johnson, Cohort VII

Reviewed and sources added by Ángel Garcia

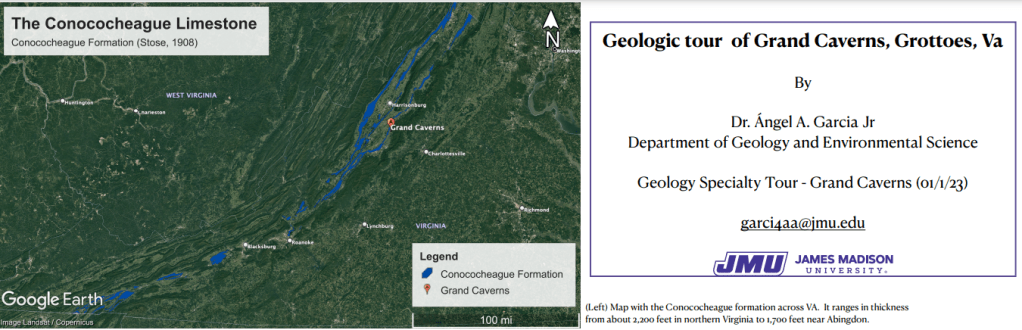

Dr. Garcia of James Madison University’s Geology and Environmental Science department generously gave us his time to guide us on a new kind of tour in Grand Caverns, which is believed to be the oldest show cave in the continental United States (in terms of being shown). It is part of the Conococheague Formation (https://mrdata.usgs.gov/geology/state/sgmc-unit.php?unit=VAOCAco%3B0) , which is comprised mainly of microcrystalline limestone with dolostone and sandstone beds with Cambrian age.

The tour began with a little bit about the term karst, which refers to the type of geology that underlies much of Appalachia. The same type of geology is found in Slovenia, which has studied karst so much that their universities offer a PhD in Karstology—very specific! The Slovenians called this structure “Kras” after their city, while the Italians pronounce it carso and the Germans say karst. In Puerto Rico, where Dr. Garcia hails from, they combine the best of all pronunciations into karso.

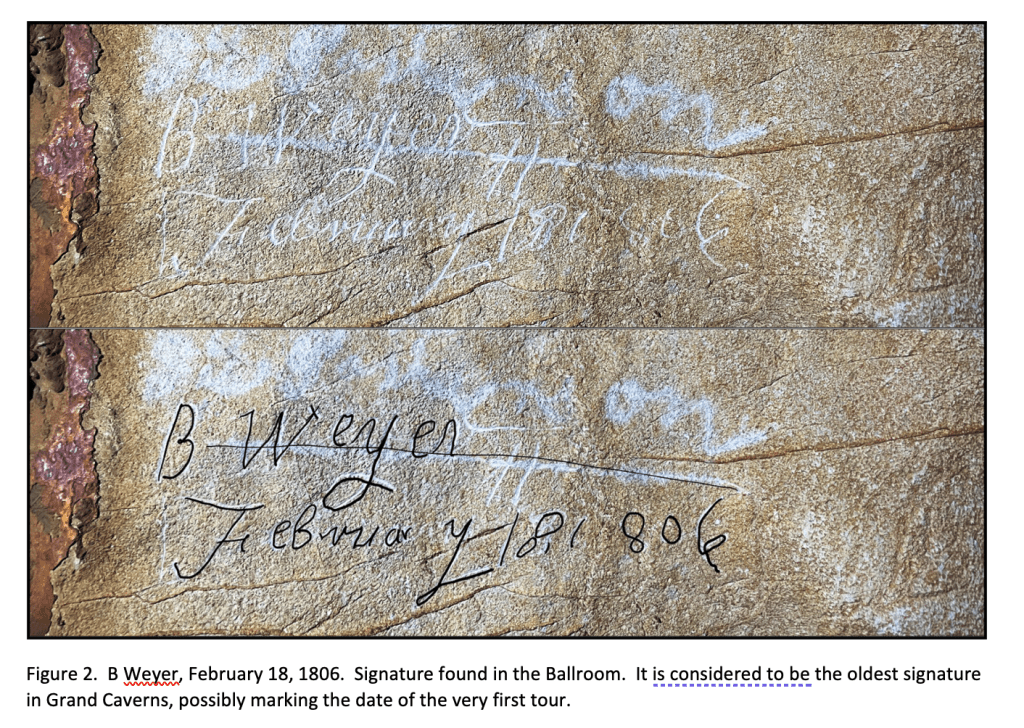

Our tour began in the original entrance, which was discovered in 1804, by a man of German descent called Bernard Weyer. It opened for tours in 1806 (believed to be on February 18th of the same year, see photo on right) and was informally called “Weyer’s Cave” until 1926, much to the chagrin of the man who owned it and would have preferred it to be called after himself!

Back in the 1800s, a tour like the one we were on would have taken 4-6 hours by candlelight. We were able to do it in a little over two hours, however, thanks to the electric lighting and the modifications made over the years to smooth out pathways and remove rocks from the halls. The old pathway was much more rugged and would have involved scrabbling over rocky debris.

Something special about Grand Caverns and other caves like it in the Shenandoah Valley is that it is a “solution cave”. This means the main agent of speleogenesis, or cave-forming, is the process of dissolution from natural waters.

Within the towering walls of the Chapel Room and Armory Room, Dr. Garcia explained that some of the rock is made of microcrystalline limestone—comprised of micro-particles so tight that water cannot penetrate between the crystals. Compression, compaction, plus heat work together to create microcrystalline structures that cannot easily break. But sandstone, which is porous, is interbedded between layers of limestone, allowing water to penetrate the layers and dissolve some of the rock to form the caverns. Another important mineral in these caverns is calcite—the white-colored deposits, which are the main component of speleothems.

In some areas, one can see “vertical bedding” and “overturned bedding” which means the rock layers have shifted to different angles rather than lying flat as they would have done originally when they were laid down by sediments. Some think of the caverns as a miniature version of the Appalachian Mountains; one can visualize how the mountains were formed in the process of folding and heaving.

Rock formations that look like flows (“cave bacon” or “drapery”) are very hard and dense—they cannot break except with a rock hammer. Dr. Garcia is particularly fond of the cave shields—rounded formations that are known as orejones, “big ears,” in the Caribbean. They look like big frisbees. Cave shields are rare in solution caves, so we are lucky that Grand Caverns contains over 500 of them throughout the known portions including both the commercial tour areas and non-public areas. The current model of cave shields is that they are formed in a similar way to stalactites and stalagmites (by dripping water depositing minerals slowly over time). [1] [2] But the rounded shape is the result of dripping coming from two different directions and meeting in the middle to form an axis.

A cave shield is formed in two halves that are separated by a hairline fracture. Dr. Garcia pointed out two different cave shields that had split in half the long way, allowing us to visualize the hairline crack that separates the two halves of the shield – like sliced sandwich bread.

While the rock formations are extremely hard and dense, the caverns also contain mud plugs—areas where clay has collected. Clay particles are not conducive to dissolving, so the cavern-type structure does not form there. Much of the mud has been removed from the public areas of this cavern so as to show off the rock formations, but in some areas, mud plugs are visible.

Next, we entered a giant space called the Ballroom, where dance parties were held during a time when women wore corsets and required fainting couches. In those days, the Great Illumination Ball was lit by 2,000 candles while musicians played. Today there are as many as 200 signatures on the rock walls indicating the guests who had toured there long ago. [3] Dr. Garcia finds it delightful to consider the layers of history here, both geologic and social-cultural. He referred to human activities like signing names or excavating rocks very tactfully as “anthropological contributions.”

In this space today, Dr. Garcia explained some of the new science that allows geologists to examine stalagmites to learn about climate change. Within each stalagmite are arch-shaped rings, much like tree rings which can be studied to measure climate change. One geologist has found a way to determine past temperatures using stalagmites as a kind of archives, also known as paleoclimatology.

Five hundred million years ago, before the Appalachian Mountains were formed, the rocks in which the caves are set in were formed under a shallow-warm, ocean. Walking down a set of steps and into another narrow room, we saw both mud plugs and more calcite. Calcite makes sparkly white inclusions in the rocks. We could see an ancient waterline along the walls of this area, indicating that much of the space had once been underwater. Dr. Garcia mentioned a study he and a colleague conducted to estimate the age at which the flooding had happened: about 670,000 years ago! It’s thrilling to see the mark of something that happened so long before human history even began. Dr. Garcia also mentioned a JMU colleague in the Chemistry and Biochemistry department who is working on a microbial library of these caverns! Iron is responsible for some of the reddish coloration of rocks. Elsewhere in the cave, green colors indicate the presence of mold or algae growing on the surface of rocks because of artificial lighting, also called lampenflora.

A lit candle in another hall flickered gently, indicating that the cave was breathing. Dr. Garcia explained that this means air must be flowing from another hall or tunnel.

Grand Caverns maintain a consistent temperature of 54 degrees F in winter and about 56 degrees in summer. In other words, there is not much communication between the surface world and the subterranean world of the caverns. [4] Additional studies have found very little change in caverns even when aboveground weather changes dramatically. There’s something reassuring about that.

Sources

[1] Hill, C.A. and Forti, P. 1997. Cave Minerals of the World, 2nd ed.

[2] Palmer, A. 2007. Cave geology and speleogenesis over the past 65 years: role of the National Speleological Society in advancing the science. Journal of cave and karst studies the National Speleological Society bulletin, 69.

[3] Lau, K., Garcia, A.A. and Yurko, K. 2022. What’s in a name? Using handheld lidar to visualize historic inscriptions in a Virginia show cave. Geological Society of America, 54, https://doi.org/doi: 10.1130/abs/2022AM-382765.

[4] Gochenour, J.A., McGary, R.S., Gosselin, G. and Suranovic, B. 2018. Investigating Subsurface Void Spaces and Groundwater in Cave Hill Karst Using Resistivity.

See more photos from Eunice Sill, Cohort 8, through Flickr HERE.

Thanks to Malcolm Cameron, Cohort III, for sharing his photos from the tour here (click on any of them to enlarge and start a slide show):